Guwahati, Dec 13: A new study from Meghalaya has found that several plants commonly used in local salads, chutneys and home remedies may play a meaningful role in lowering blood pressure—offering low-cost, food-based support against hypertension, one of the leading risk factors for cardiovascular disease worldwide.

The study, conducted by Rebecca Marwein, Matsram Ch Marak and Lakhon Kma of the Department of Biochemistry, North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU), Shillong, reviews scientific evidence showing that traditional plants consumed by Indigenous communities across Meghalaya possess properties that support vascular health and blood pressure regulation. The findings have been published in the NEHU Journal.

Hypertension remains a major driver of preventable deaths globally, with cardiovascular disease rates rising sharply in India over the past three decades. Meghalaya reports particularly high prevalence among older adults. While modern antihypertensive drugs are effective, the researchers note that long-term use can be costly and is often associated with side effects—making dietary and preventive approaches increasingly important.

The NEHU review focuses on a range of plants that are readily available in local markets and kitchen gardens and are routinely eaten raw, lightly cooked or prepared as decoctions.

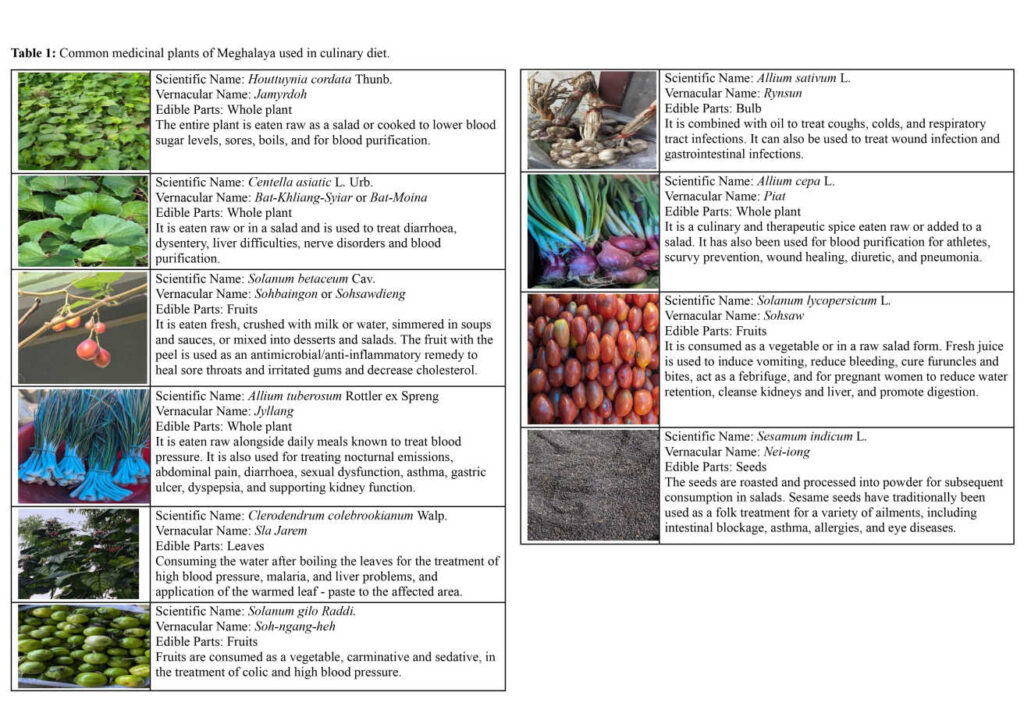

Among the key plants identified are Houttuynia cordata (Jamyrdoh), a popular raw salad herb rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds that enhance nitric oxide availability and help relax blood vessels, and Centella asiatica (Bat-Khliang Syiar), widely consumed as a salad green and known to improve vascular function.

The study also highlights the cardiovascular benefits of common Allium species, including garlic (Rynsun), onion (Piat) and Chinese chives (Jyllang), which contain sulphur compounds and flavonoids that reduce arterial stiffness. Several Solanum species—such as tomato (Sohsaw), tree tomato (Sohbaingon) and bitter brinjal (Soh-ngang-heh)—were found to provide potassium, lycopene and antioxidants linked to blood pressure regulation.

One plant of particular significance is Clerodendrum colebrookianum (Sla Jarem), traditionally used by Khasi and Jaintia communities to manage hypertension. The review notes that experimental studies support its strong vasodilatory effects. Sesamum indicum (Nei-iong), commonly used in roasted or paste form, was also highlighted for its lignans, including sesamin, which help regulate cholesterol and blood pressure.

A notable aspect of the study is its emphasis on food synergy—the interaction of plant compounds when consumed together. Many traditional combinations already present in Meghalaya’s cuisine, such as tomato with Jamyrdoh, bitter brinjal with roasted sesame, gotu kola with onion, and Sla Jarem with garlic, were found to enhance the bioavailability and effectiveness of key phytochemicals.

The review explains that sesame oils aid the absorption of fat-soluble compounds, while flavonoids such as quercetin from onions can increase the activity of triterpenoids found in gotu kola. These interactions may significantly amplify antihypertensive effects compared to consuming individual plants in isolation.

The findings add to growing scientific interest in Indigenous food systems as culturally grounded and affordable strategies for managing non-communicable diseases. For Meghalaya, the researchers suggest that integrating traditional salads and plant combinations into dietary guidance could offer a practical way to reduce hypertension risk at the community level.

The authors emphasise that exploring these traditional plant combinations could lead to new plant-based interventions tailored to Meghalaya’s cardiovascular health needs, while also informing culturally relevant dietary guidelines and future pharmacological research. By bridging Indigenous knowledge with modern science, the study points towards sustainable and locally accepted approaches to hypertension management.